pizza and prototypes: my time at X, the moonshot factory

Around a month ago, I had the amazing opportunity to spend two weeks with 17 other students at X, Alphabet’s moonshot factory. In that time, I:

- tried solving air pollution,

- met approximately 1000 PhDs,

- burned enough incense to max out an air quality sensor,

- accidentally made lightning,

- and pitched Project Dusbuster to the CEO (sorry, Captain of Moonshots) of X.

I was also fed very well by the Alphabet kitchens. I'd like to share some stories and thoughts from my time there, and maybe you can tell me if I learned anything.

A special thank you to Jillia Fongheiser and Nabeela Virji for all your work making this experience life-changing.

parfait:

Day one, we walk into X, meet and thank Jillia, and walk into the cafeteria for breakfast. Before X, my top thought was not the food I’d be having. But I'm still human, and I'll admit to a single moment of weakness. Maybe multiple.

There were so many options! This paradoxically made my food choices worse. Look at my first breakfast:

4/10, lacks intention and forethought.

It's certainly not a bad breakfast. But it’s obvious that something is missing. Half the plate was empty because I didn’t know where the bread was.

Too many choices was a common theme. Our time at X was split between learning about X and making our own moonshots; between pure structure and pure chaos. One of the hallmarks of moonshot thinking is freedom — many of our sessions were dedicated to shaking off the artificial constraints stopping us from thinking 10x. We were told that we could, within health and safety guidelines, do anything.

Do anything. That phrase has sat in my mind since I left. I've heard it so many times in “motivational” speeches, but the phrase takes on a very different flavour when I'm in the office that recently killed (and open-sourced) a project that harvests water from the air, and that shares office space with cars that drive themselves.

When you can truly do anything, almost every choice is suboptimal.

X is full of tensions. One of them from their onboarding guide is “embrace dynamic stability.” Lean too far in one direction and you’ll tip over; keep moving, and you’re fine. I was scared of the bicycle, scared of doing it wrong and falling and failing. The first day ended with an AMA with Eugenie Rives. In response to my question, she looked me dead in the eyes, peered into my soul, and asked me “have you ever failed?” She challenged me to, in my two weeks, have the biggest failure possible. If my goal was to fail, what was there to be afraid of?

It’s theoretically easy to figure out what to do — do something and iterate from there. But thinking about moonshots in the abstract is, in my opinion, basically impossible. The actual feeling of staring into that totally unconstrained space, unbounded by thoughts of practicality, without any anchors or guides, just an unqualified guy floating in space — the panic builds the longer you spend adrift.

Thinking is much easier to do when doing. When you have an anchor, an inroad, a foothold, it's easier to get your train of thoughts on the rails. Staring blankly in the middle distance trying to think of ideas is not a very good recipe for ideas. Another piece of advice from our onboarding: “be like a tiger beetle.” Tiger beetles pick a direction, sprint so fast that they can’t change direction, and then stop and reorient. Pick a direction, and start moving.

Did I fail as big as possible? Probably not. But the big secret is that the first step doesn’t really matter, just so long as I take it. Our team’s first idea was something something desalination ocean acidification — not remotely close to what we worked on. Those first explorations provided a foundation to stand on. Just like how I eventually discovered that I could make a parfait and have all my breakfast bases covered. With that as my anchor, I was free to explore without worrying.

Is this a crude analogy? Yes. Is choosing breakfast as hard as coming up with a moonshot? No. But the same principle is at play, and that staple parfait every day gave me the stability I needed.

waffle:

Probably one of my favourite meals at X was the waffle. For one, I've never used a waffle iron before. For two, it kind of felt like that day in kindergarten where we had waffles for breakfast on pajama day, except I couldnt make my waffles mickey mouse-shaped. And I wasn't wearing pajamas. And I had work to do. Okay maybe it's not that similar but whatever, I really needed the joy of that waffle. Wednesday was when work on the actual projects would start, and thus started the most difficult part of my week.

There's only one reason that can succinctly explain why I felt the way I did about my moonshot work: I'm lazy. I'm going to refuse that explanation for now.

As soon as we chose our teams and started working on the moonshots, everything got all serious. Timelines, deadlines, notions, headings, subheadings, subsubheadings — I was trapped in some kind of hell. Suddenly my self-imposed top concern should be winning, whatever that means. I didn't know what to do, but I was also too constrained. I needed to do things, but everything I did felt like the wrong thing.

I guess in that fervour I forgot a very core attribute of moonshots: they're hard.

Wait what?

There was a 0% chance we would complete a moonshot in our two weeks. We would all fail. And that was the point. Astro (Captain of Moonshots at X) gave us this frame: what would you do if you knew you would fail?

I talked to three separate people, all of whom know me very well, and they all said: just have fun. Me being the person I am, and X being the type of place that it is, having fun was an amazing heuristic for deciding what to do in each moment. It freed our team from the trap of winning. What did we want to build? Who did we want to meet? If we looked back on this experience 5 years down the line, what would we want to have done?

Whatever I chose to do, it would be hard. X isn’t the place to do easy things. So if i’m going to do hard things, why do them because I “had to” — I want to do them anyway!

There are asterisks to having fun. Of course there are. But for where I was and how I felt, the advice worked. I got a deep understanding of our problem in a short amount of time, we got to build a prototype, and I learned so much from so many incredible people. I loved my time at X. it was as easy as choosing to love it:)

pizza:

If you asked me about something that surprised me about X, I would have a lot of answers. In the spirit of having fun, here’s the least important surprise: the pizza is amazing. Probably my single favourite non-breakfast food item in large part because of how unorthodox some of the varieties were. Someone later pointed out to me that the pizza often featured leftovers from the day before — that’s genius!

even the awfully cropped and low-res pizza is making me hungry.

In the spirit of leftovers on pizza, I want to talk about all the ideas our team rejected. Each of these ideas answered a question we thought needed answering. We had to either find an answer or disregard the question every time we killed an idea.

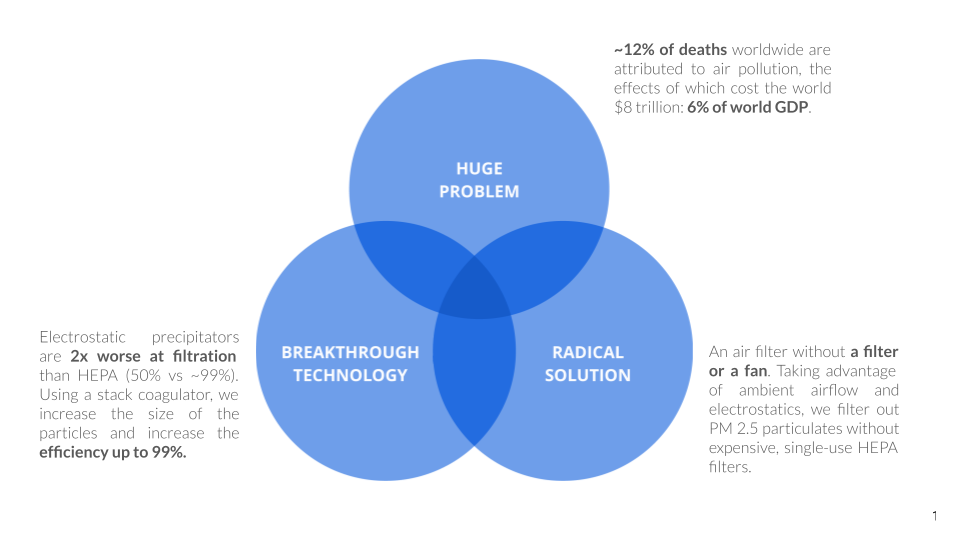

I can no longer avoid talking about what our moonshot actually is. Here is the venn diagram with the three core pillars of a moonshot. This is the single most important product we produced, more than the prototype and more than the entire rest of our presentation. Without this, we have no moonshot.

Our inspiration started from the problem. The major cause of adverse outcomes relating to air pollution is particulate matter, especially particles less than 2.5 microns (called PM 2.5). These particles are correlated with COPD and asthma, and are also bad in a variety of other, more subtle ways (like everyone’s favourite: smog). 1

Here’s a list of all our failed ideas for getting rid of these PM 2.5 particles:

- A nasal/throat implant

- A net/filter attached to a drone

- A filter inside a drone

- A filtration balloon

- A really big tower

- A whole bunch of regular (indoor) air purifiers

- A spray that traps pollutants (febreze but for pollution)

- Metal organic frameworks

- “Brush electrostatics”, whatever that is

- An army of low-cost sensors for monitoring

- A really big tower, but this time it looks like this and is solar powered (thanks Sam!)

- A biofilter that eats pollutants and produces fertilizer

- A reactor that takes pollutants and produces hydrogen fuel

So much of what drove our ideation was conversation with the amazing X-ers we got to meet. If you want the real answer of what surprised me about X, it was how different all the people are. Everyone had a unique background, interesting stories and a fresh perspective on whatever we were struggling with. S tier people, just like the pizza.

How did we use our leftovers? these all answer one of the following three questions:

- Where do we filter the air?

- How do we filter the air?

- What do we do with what we’ve filtered out?

Here's the same list, updated with some context. Feel free to skim.

- A nasal/throat implant [where]

This is a pretty big behaviour change to ask for. It would have to be cleaned and replaced. The death blow: it would need to compete with a cheap and easy alternative that is a mask. The existence of masks invalidates most individual-level interventions.

- A net/filter attached to a drone

- A filter inside a drone

- A filtration balloon [where]

I'm grouping these together as our airborne ideas. Our target is cities, which have very constrained airspace (buildings, power lines, regulation etc.). The idea of balloons floating in the air like bubbles is really appealing but, in the spirit of Nick Foster, the future is a little bit broken. What happens when they get caught in power lines?

- A really big tower [where]

The perfect place to build a really big tower is obviously in the places where real estate is the most expensive. Cut for cities reasons.

- A whole bunch of regular (indoor) air purifiers

This is the status quo, we’d love it if they were awful. Thankfully they are awful: they need constant power, make a lot of noise, and you have to pay 10% of the upfront cost every 6 months to replace the HEPA filters inside them.

- A spray that traps pollutants (febreze but for pollution) [how]

According to this paper and various other less formal sources, smog is caused by PM 2.5 particles getting coated in water and clumping together, eventually becoming visible and hence causing smog. Let’s not cause smog.

- Metal organic frameworks [how]

They’re expensive and it’s pretty hard to beat HEPA filters on filtration efficiency. HEPA is already at a very high standard, so getting better filtration isn’t that important. Also, can someone tell me what these are?

- Brush electrostatics [how]

We took apart an air purifier and found out that it’s literally a little bristle of fibers. As far as I can tell, it splits water into H+ and OH-, which attach themselves to pollutants alternately, charging them positively and negatively so that they stick together. We used this idea’s spiritual successor, a stack coagulator.

- An army of low-cost sensors for monitoring [where]

This already exists.

- A really big solar uptake tower [how]

As cool as this is, it’s still a really big tower.

- A biofilter that eats pollutants and produces fertilizer

- A reactor that takes pollutants and produces hydrogen fuel [what]

PM 2.5 particles are really small, and there isn’t much of it even in very polluted air, making it hard to make any meaningful amount of product. There's so little of it that disposal really doesn’t matter (it’d take ~ 10 years to fill a cubic meter of storage). Also, the chemical composition can vary based on the source, which makes it even harder to have any consistent chemical process.

That's everything we didn’t do. What did we do in the end?

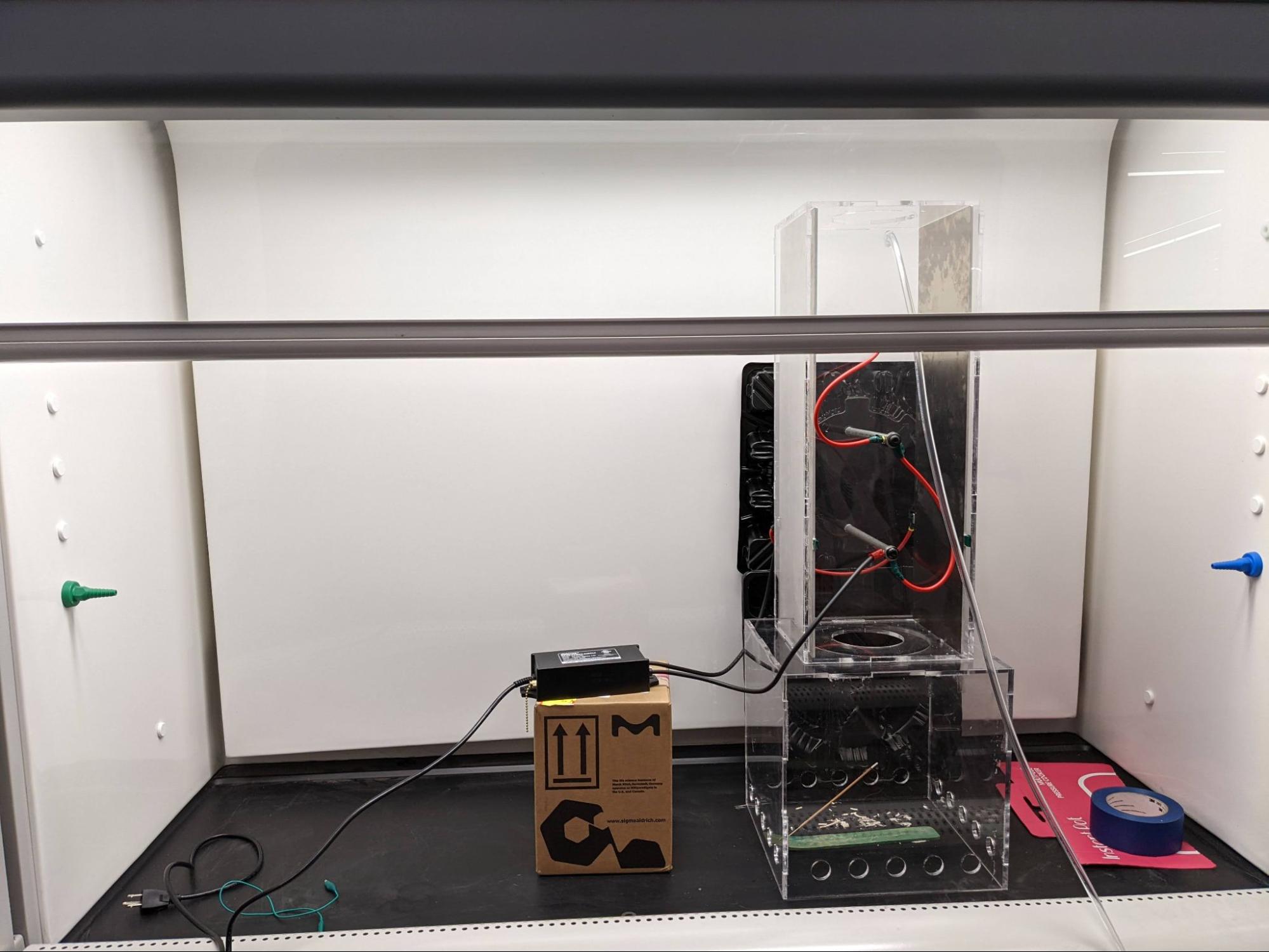

That's our prototype! The fundamental piece is the thin box on top. There are three aluminum rods in the center and two aluminum plates. The rods are positive electrodes, and the plates are negative electrodes. between them is a 10 kV potential difference. The strong electric field pushes the particles, most of which are either charged or polar, towards the plates. They stick to the plates and are thus no longer in the air.

The aluminum plates were cut using water jets (thanks Luke!). The acrylic was laser cut (thanks Jonathan!). We were thankfully not allowed to wire up the high-voltage power supply — that job is due to Joe. Don’t tell anyone, but there was an exposed bit of metal that started arcing during our poster session. It was a little cool that we made lightning. Luckily we had electrical tape on us.

The bottom box is part of our testing rig. We tried to burn a variety of materials to generate PM 2.5, eventually settling on incense (thanks Alex!). Incense was so effective that we maxed out our sensor the first time (at around 3000x the recommended level; don’t burn incense in poor ventilation). We burned incense and turned on the fume hood for air flow, then turned on our filterless filter. By our very crude analysis (the raw data off the sensor didn’t come in a time series), the PM 2.5 levels dropped by ~25%. It worked!

Our fully realized prototype would use a wind turbine that would create airflow from ambient air currents. Fans are loud, expensive and draw a lot of power — without a fan, our power draw is minimal and easily covered by solar. Our solution would also first charge half the particles positive and half the particles negative (this is the stack coagulator), making the particles bigger and theoretically increasing the efficiency of our filter.

The experience of building a prototype in X’s Design Kitchen was incredible. If there's anywhere where leftovers are used the most, it’s in the DK. The aluminum rods were cut from one long leftover piece, tapped and deburred by us. The original fan we used was a PC fan that was just lying around. The sensor was borrowed from the health and safety team (thanks Jenny!). One of X’s core pillars is being scrappy, and we experienced that firsthand — in both the pizza kitchen and Design Kitchen.

blueberry scones:

We've arrived at dessert now. Are scones dessert? They were served at breakfast. But they were my favourite dessert. I took a box of scones to our work rooms for whenever we needed something to cheer us up.

I have no fancy metaphor for this, but I'd like to thank everyone that helped this experience be as amazing as it was.

Thank you to Luuk for being the best sponsor. We loved your whiteboard message <3

Thank you to Nadeem for activating this experience for us.

Thank you to Damian, Navid and Alisha for supporting and coaching us.

Thank you to everyone at TKS for making this a reality for me.

Thank you to Joe, Luke Gray, Alex Grauberger, Jonathan, and Alex Ramadan for all your help in the DK. Working with you was awesome!

Thank you to Sophia, Taira, Naila and Alex for being amazing teammates:)

Thank you to Eugenie, Benoit, Nick Foster, Antonio, Nick Sexauer, Ray, Asmau, Greg, Julie, and all the other session leaders for letting me learn from you.

Thank you to Astro and everyone at X for welcoming us into the factory,

And thank you again Jillia and Nabeela for running this experience for us. It was incredible! I hope to be back one day:)

Footnotes

-

we repeatedly came across the stat that indoor air quality was 2-5x worse than outdoors. i couldn’t trace that fact to any study or reputable source — if anyone knows where this came from, let me know) ↩